Mikael Agricola, who lived in the early 1500s, is credited with creating the first comprehensive writing system in a Finnic language. He is even called "The Father of literary Finnish." However, the

birch bark letter no. 292, created over 200 years before Agricola, is the oldest known document in any Finnic language.

In addition, inscriptions in

Old Permic script are among the oldest relics of the Uralic languages. To set the exact date of Komi writing is impossible. But the fact that it originated long before the 10th century is evidenced by the

Books of Ahmed Ibn Fadlan about his journey to the Volga in 921-922. Arab traveler and secretary of the embassy of the Baghdad Caliph wrote about the correspondence of the king of Volga Bulgaria with the ancestors of the Komi people, calling them Vysu (

вису).

The Komi ancestors did not have one, but

two kinds of writing. The first is the so-called practical letter of the pass, or symbol. With these signs, the zyryane (Komi) tagged their belongings and hunting grounds, and also made calendars. Similar signs existed among all Finno-Ugric and Samoyed peoples. Almost without changing, these icons endured to modern times on spinning wheels, as well as embroidered and knitted patterns.

Komi Calendar Passes

Georgy Lytkin wrote about the difference between the two types of writing in the 19th century: “Zyryan passes never had the meaning of letters, they cannot convey what the Egyptian hieroglyphs conveyed. No approach can be made between passes and stefanovsky letters.” Unlike the Komi passes collected in the 19th-20th centuries,

tamga-like graffiti on archaeological finds belong to the 12th-14th centuries. They are undoubtedly the oldest of such signs.

http://foto11.com/komi/docs/komipas.php

Stepan Khrap of Perm (St. Stephen) is said to have created Old Permic script for the Komi language in 1372. Actually, all he did was employ a script already well known to him. His grandfather, an educated Komi merchant Dzebas, often climbed up Vychegda and Vym in his trade affairs. It was then that he would have seen for the first time the Komi letters that Zyryan merchants used in trade.

http://www.komi.com/mc/arhiv/new001.htm

Stephan of Perm

This occurred a century

before the creation of the Voynich manuscript (according to carbon dating), and roughly two centuries before Agricola and his writing system.

Not until the 17th century was Old Permic, aka

Abur, superseded by the Cyrillic script from which it was loosely adapted. I say "loosely" because Old Permic is called a "highly idiosyncratic adaptation" of Cyrillic and Greek, with Komi "Tamga" signs. Interestingly, since not many persons knew it, Old Permic was also used as cryptographic writing for the Russian language.

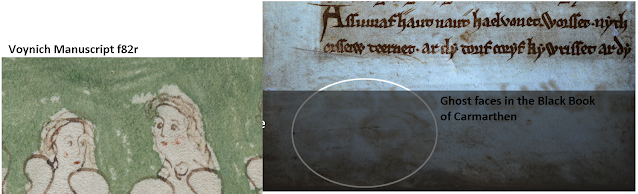

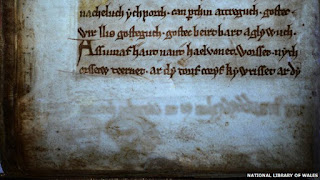

Could the Voynich manuscript use the Komi's two writing systems, the Tamga system for f66v and f57r and for the rest of the text the more formal writing system employed by the Komi to send letters to trading partners like the Bulgar king?

Let's take a look at Old Permic script, especially Old Permic cursive, and compare it against the script in the Voynich manuscript used for what appear to be 1) a list of rune charms and 2) a calendar.

Pronounced correspondences occur on two pages, one possibly listing

runic charms and the other on what appears to be a seasonal calendar. The rest of the manuscript appears to employ, however strangely, more of a Latin script. The characters which appear similar to Old Permic are not used throughout the manuscript but rather in special, isolated places, as if they were runes or numerals. They in fact do have quite a few correspondences with Tamgas, those used in Finno-Ugric culture.

Here is a comparison between Voynichese, Hungarian Tamga-like symbols, and the Old Permic writing system.

If the Voynich manuscript has been influenced by an obsolete script from the Perm Krai, and if its folios contain words from inhabitants of the Perm Krai, then perhaps there are extant records of

folk songs that would bear resemblance to the frequently repeated words in the Voynich manuscript.

So then, we have this:

One striking correspondence is that the above wedding tune from the Vatka Komi in the Krov district, uses the letters that, if my transcription is fairly accurate, are found in abundance in the Voynich manuscript: a, u, o, i, e, s, p, t, k, m, and l. In addition, it repeats small two-letter words: oi, pe, ok, and uk.

Other correspondences exist regarding Komi mythology, folk costume, and lore.

Power over water

Mythic focus on women

Zarni Ań (Golden Woman) was the supreme goddess of the Zyrian people (Komi).

"In the mythologies of Uralic peoples, a woman is seen as the ruler of life and death and the southern and northern direction of the corresponding air directions," says Academy Professor Anna-Leena Siikala."

The gods of the shamans are the gods of nature

Depictions of female suns

Päivätär ('Maiden of the Sun'), is the goddess of the

Sun in Finnish mythology. Described as a great beauty, she owns the silver of the Sun, spins silver yarns, and weaves clothes out of them. In Kalevala, young maidens ask Päivätär to give them some of her silver jewelry and clothes.

Professor Anna-Leena Siikala finds it possible that Päivätär was a goddess who ruled over life and light. During Christian period, she was replaced by Virgin Mary.

Symbols of spinning and weaving

Not only was Päivätär a goddess—she was the goddess of

spinning, and her sister, Kuutar, goddess of the moon, was in charge of

weaving.

|

| Komi Women |

Conclusion

Thus, we find shared nuances in script, mythology, and symbolism between the Voynich manuscript and Uralic culture, especially among the people of the Perm Krai.