Above is an example of myriad Medieval manuscripts to be found within the golden hoard of Norse literary tradition. This Icelandic manuscript dates from the 14th century and was created by the Icelander Haukr Erlendsson. It recounts Eiríks saga rauða or the Saga of Erik the Red.

Medieval Norse history is inextricably woven into the history of the northern British isles because quite early on as well as Scandinavia the Norse settled there in substantial numbers. The culture of Orkney, for example, may be said to be far more Norse than that of Britain south of Hadrian's Wall. This is good to keep in mind when studying the Voynich manuscript because the script closest to it hails from Scotland.

Perhaps you came up with saPro.

This word in fact does not come from the Voynich at all but rather from a letter that gained some renown in June of 2013 for its re-identification as being written by Robert the Bruce to Edward II. It was originally attributed to Robert's son.

Here it is in full.

The word above is, in fact, Latin.

Had it been written in a far more obscure tongue, scholars might still be stumbling about with its transcription and translation, but since it is Latin, the translation came rather easily, especially compared to the Voynich.

Take a look at some other words in this letter from Robert the Bruce, written roughly a hundred years before the Voynich.

Here's just a snippet from the Voynich.

Since it's in Latin, the letter "k" is at best scarce in Robert the Bruce's letter and may be completely absent, just as it appears to be in the Voynich. Rather, the "k" sound, if it appears, is presented as double c's as in ecclesie. Here's some Wiki on it.

In the earliest Latin inscriptions, the letters C, K and Q were all used to represent the sounds /k/ and /g/ (which were not differentiated in writing). Of these, Q was used to represent /k/ or /g/ before a rounded vowel, K before /a/, and C elsewhere. Later, the use of C and its variant G replaced most usages of K and Q. K survived only in a few fossilized forms such as Kalendae, "the calends".

When Greek words were taken into Latin, the Kappa was transliterated as a C. Loanwords from other alphabets with the sound /k/ were also transliterated with C. Hence, the Romance languages generally use C and have K only in later loanwords from other language groups. The Celtic languages also chose C over K, and this influence carried over into Old English. Today, English is the only Germanic language to productively use hard C in addition to K (although Dutch uses it in learned words of Latin origin and follows the same hard/soft distinction in pronouncing such words as English).

But let's say that in the Voynich, the language used is very fond of k's yet the writers are more familiar with (or have only an example of) Latin script. What they may do is for every k they wish to write pen a pair of c's.

The Handwriting

|

| A manuscript written in Sweden at about the time the Voynich manuscript was written. |

|

| Detail from 'The Mirror of the Life of Christ', an illuminated 15th-century Scottish manuscript. |

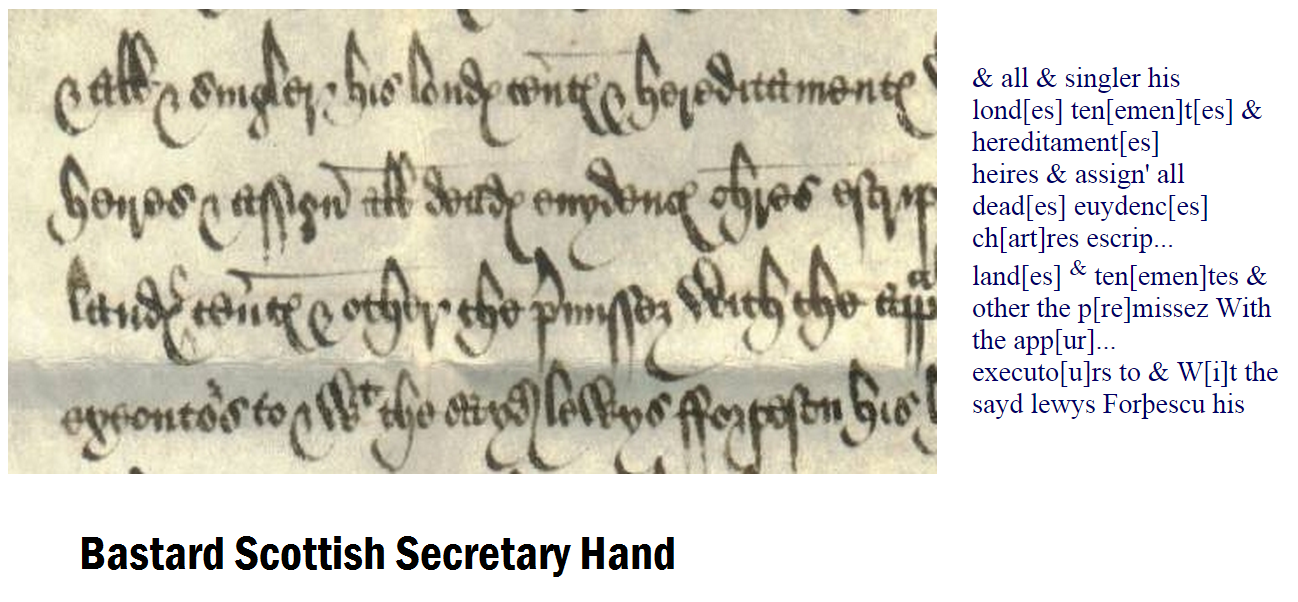

Below is a Register of Sasines for Glasgow, 1654-1656, written in Scottish secretary hand and taken from a superlative site on the subject, Scottish Handwriting.com. If you can read this without looking at the transcription, then you're on the road, at least, to reading the Voynich manuscript.

The words, of course, are Scots, not the language used in the Voynich, but if you transcribe a passage from the Voynich using letters from this alphabet, you get something strongly suggesting an arcane Fenno-Norse origin. The secretary hand was developed a century after the Voynich was written, so it would be absurd to say that the Voynich was written in Scottish secretary hand. In fact, it may be the other way around. Whatever hand this is in the Voynich may have heavily influenced the development of the Scottish secretary hand.

But how on earth, you might ask, did an arcane Fenno-Norse language end up written in a hand related to one used centuries later in Scotland?

A stigma has arisen against the Scots perhaps starting with the Romans, who became so sorely frustrated with them. By the time of the Glorious Revolution, especially the Scots in the Highlands were deemed for the most part incorrigible and illiterate. The potshots that Westminster takes to this day at the Scots (who have recently dared to clap in that non-clapping place) reflect this centuries-old stigma.

Since, like the Nordics, Scottish culture was not imbued with Judeo-Christian or Greco-Roman culture but something quite different, it was next to impossible for those south of them to admit they had any culture at all. (This is akin to researchers today clinging habitually to the canon to try to interpret the Voynich manuscript and shoehorning the imagery into explanations that they are familiar with in lieu of waking up to the presence of another, completely different culture which more than likely birthed it.)

It is good to keep in mind that Scalloway, Shetland, is a hundred miles closer to Bergen, Norway, than it is to Edinburgh. Especially in northern Scotland and most markedly across Orkney and Shetland, the Norse have had far more of an influence on Scottish culture than any people south of Hadrian's wall. The Scots language can be traced back to mainly Norse origins. For centuries the people on either side of the North Sea have traded, the Finns and the Sami being frequent visitors, along with north Germanics, and, going back all the way back to the Kvens up to the 15th century, nordic aristocrats owned tracts of land in north Scotland.

But how on earth, you might ask, did an arcane Fenno-Norse language end up written in a hand related to one used centuries later in Scotland?

A stigma has arisen against the Scots perhaps starting with the Romans, who became so sorely frustrated with them. By the time of the Glorious Revolution, especially the Scots in the Highlands were deemed for the most part incorrigible and illiterate. The potshots that Westminster takes to this day at the Scots (who have recently dared to clap in that non-clapping place) reflect this centuries-old stigma.

Since, like the Nordics, Scottish culture was not imbued with Judeo-Christian or Greco-Roman culture but something quite different, it was next to impossible for those south of them to admit they had any culture at all. (This is akin to researchers today clinging habitually to the canon to try to interpret the Voynich manuscript and shoehorning the imagery into explanations that they are familiar with in lieu of waking up to the presence of another, completely different culture which more than likely birthed it.)

It is good to keep in mind that Scalloway, Shetland, is a hundred miles closer to Bergen, Norway, than it is to Edinburgh. Especially in northern Scotland and most markedly across Orkney and Shetland, the Norse have had far more of an influence on Scottish culture than any people south of Hadrian's wall. The Scots language can be traced back to mainly Norse origins. For centuries the people on either side of the North Sea have traded, the Finns and the Sami being frequent visitors, along with north Germanics, and, going back all the way back to the Kvens up to the 15th century, nordic aristocrats owned tracts of land in north Scotland.

Below is a record from the county court of Chester, held on Tuesday after the feast of St Nicholas in the year 1310. It lists a fellow by the unfortunate name of Roger Fuckbythenavel preparing to be outlawed. This is so far the earliest sighting of the swear word in the English language. What is even more interesting for our purposes is the court hand in which the record was written. Note that the f appears as a double f and the l has two bizarre little top loops. In addition, the e is extremely rounded. Finally, the u and the v are identical.

Here is an example of how the smoke screen about Scottish culture has been recently lifting. A researcher at the University of Glasgow has discovered the oldest surviving non-biblical manuscript from Scotland. Although the Boethius manuscript (the 'Consolation of Philosophy') which dates to c.1130-50, was known and had previously been catalogued, scholars had believed it to be English, with Durham being the most likely place of origin. However, closer inspection has revealed that the manuscript's handwriting and illustrations do not match those of Durham, or other English books, from this period. Identifying the manuscript as a product of David I's Scottish kingdom means that Boethius was being read in Scotland 300 years earlier than previously thought. Dr Murray, who is conducting a British Academy Post-Doctoral Fellowship project on Boethius's 'Consolation of Philosophy' in Scotland, believes that this is proof that intellectual and literary cultures were flourishing in Scotland at a far earlier date than has been realised.

The Voynich derives from a medieval progenitor of Scottish Secretary Hand. The language is not Gaelic, but it is a combination of proto-Germanic and proto-Finno-Ugric, possibly a rare survivor from the Kvens.

Perhaps you can see now, these is indeed a context for the Voynich manuscript's actual script. It's simply of course in a more obscure tongue than Latin and in a far more delicate hand than that of Robert the Bruce.